TUCSON, Ariz. — Go outside on a clear night and count the stars.

Chances are you’re not seeing as many glittering points of light as you did as a child unless you live in a pretty secluded area.

John Barentine of the International Dark-Sky Association addresses the Vatican Observatory’s Faith and Astronomy Workshop. (CNS photo/Dennis Sadowski)

Humans, through all their progress, have lit up the planet so much that we’ve forgotten how magnificent a truly dark night sky can be. It’s only changed since 1879, when Thomas Alva Edison invented the light bulb.

The International Dark-Sky Association is working to alert and educate people, primarily in the United States and Europe, about the loss of the legacy of dark skies.

John Barentine, program manager at the Tucson, Arizona-based association, spent an hour at this month’s Faith and Astronomy Workshop sponsored by the Vatican Observatory, discussing how the natural night sky is under threat from the drive to light up the night in our communities.

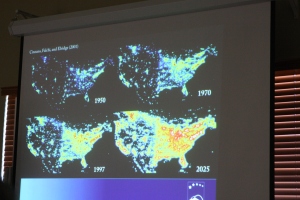

By 2025 half of all U.S. residents will be living in perpetual twilight at night if current trends of electrification continue, Barentine said.

A slide produced by the International Dark-Sky Association depicts the advance of lighting across the U.S. since 1950 (CNS photo/Dennis Sadowski)

To illustrate his point, he showed before and after images of cities as seen from Earth orbit that are converting existing

street and security lights to energy-saving LED lighting. The photos showed how the blue-rich white LEDs obscure the landscape below. The International Dark-Sky Association fears that because LEDs use far less energy, cities will resist shielding the new lights to prevent photons from being scattered upward into the atmosphere.

Association staff members have worked with cities to show how LED lighting also can be a detriment to safety. The glare produced by unshielded lights actually limits a person’s ability to see what lurks in shadows, Barentine said as he produced a photo illustrating his argument.

The International Dark-Sky Association has developed model lighting legislation for cities, but has met with limited success. In places such as Tucson, where astronomy is a significant industry, standards limiting light pollution have been enacted.

However, Barentine noted, astronomers at Kitt Peak National Observatory 50 miles southwest of the city are more concerned that the glow of lights from ever-sprawling Phoenix 150 miles away now pose a greater threat to observing.

A professional astronomer, Barentine also pointed to studies that showed people exposed to a constant level of light — from cellphones, night lights or other round-the-clock lighting — have developed uneven sleep habits that can lead to other health issues.

Excessive night time lighting also disrupts the natural world. Migrating birds, which often use the moon and stars to guide their flights northward or southward, are among the animals most widely affected by bright lights. Scientists have discovered that birds often become confused by brightly lit buildings and fly around and around them until they drop from exhaustion. Sea turtle hatchlings are affected because they head onshore instead of to the ocean after birth.

The steps needed are difficult to undertake, Barentine admitted.

“It’s more than turning off the lights,” he said. “It’s getting people to think differently.”

Change will come through education and demonstrating how darkness benefits the planet, he told the workshop.

Pope Francis’ encyclical “Laudato Si’, On Care for our Common Home,” even mentioned the need to turn off unnecessary lights, he added.

He also invited the workshop to join citizen science efforts focusing on the need to change lighting practices.

Barentine left workshop participants with five steps to consider:

— Identify dark skies as valuable.

— Improve lighting within your control.

— Talk with your neighbors about their lighting practices.

— Write or call elected officials to change public policy.

— Speak out.

“If we don’t know there’s a problem to be solved,” he said, “we won’t fix it.”